Is Continuity Key? | A Brief Analysis of America's Educational Policy Approach

In our previous article, Professor Fernando Reimers provided numerous examples of policy-driven approaches to education across the international community, demonstrating varying degrees of efficiency and effectiveness.

Singapore, in particular, has emerged as a global leader with respect to these qualities and has successfully developed a consistent K-12 programming regimen oriented towards an explicit set of objectives.

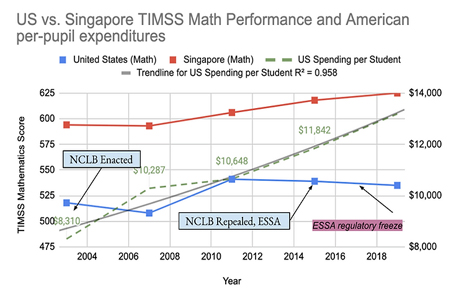

Professor Reimers cited a broader trend of the Singaporean government’s continuity in policy as the primary factor behind the nation’s rapid ascent in education. Relative to the United States and other Western countries, its infrastructure is young – the K-12 system did not begin to evolve into today’s marvel until the 1980s, by when Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s economic reforms had enabled the country to prosper and shift government focus towards investing in educational quality. Focused efforts such as PM Goh Chok Tong’s “Thinking Schools, Thinking Nations” vision, resulted in immense success towards the turn of the century, as quantified by consistent strong performance on international standardized testing (eg. the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)) over the past decade.

In comparison, the United States began approaching educational quality reforms two decades prior to Singapore’s initiative, signaled by the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Though President Lyndon Johnson touted the legislation as a cure to the achievement disparity between students of different socioeconomic circumstances (notably the rural-urban and racial divides, analyzed in the 1966 Coleman Report), the act’s rollout did not occur as intended by the federal government:

Despite the enactment of the ESEA, the nation continued to witness educational disparities among students of different backgrounds. A crucial moment for reform came in 1983, with the publication of “A Nation at Risk” – a report from the Department of Educational Excellence that raised the alarm on American schools falling behind those of international competitors, and employed ominous language such as the infamous line: “the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity.” In subsequent years, it was criticized for its exaggerated rhetoric and marred by revealed inaccuracies (for example, a statistical paradox was behind the misleading claim that SAT scores were on a downward trend). Nonetheless, many educational policy experts revere it for bringing educational issues to the national political stage, thus prompting reform efforts.

Following the Reagan era, the sentiment of widespread academic underachievement continued to ring in the ears of policymakers. This culminated in the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), which significantly expanded the federal role in education and increased local accountability for student achievement with mandatory testing. However, the assessments and standards varied by state, and many local governments resisted the act’s mandates. This phenomenon (coined the “state rebellion” by Harvard GSE’s Professor James S. Kim), undermined the bill’s effectiveness, and by the mid-2010s, the build-up of bipartisan NCLB criticism led to its 2015 replacement, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). The ESSA marked a considerable federal retreat from education and placed states in charge of accountability systems. In 2017, a GOP-led legislative push in Congress further repealed accountability regulations from the ESSA.

One can argue that the Singaporean approach to education would be inappropriate and unsustainable for a nation as diverse as the United States. However, the inconsistent and tumultuous nature of education policy (which has increasingly fallen victim to political polarization in recent years) has left schools and educational bodies without direction. In a Brookings Institute article, Kenneth K. Wong (Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy) asserted:

“State-level governance will offer opportunities and challenges for educational progress in 2022. Education policy will be influenced by the substance and rhetoric in the electoral process across states throughout this year.”

Professor Wong’s analysis indeed reflects the various possibilities that exist for the direction of K-12 education as the matter lies in the hands of local authorities, as well as its volatility in relation to politics.

Sources

- theconversation.com

- Guthrie, James W., and Matthew G. Springer. “‘A Nation at Risk’ Revisited: Did ‘Wrong’ Reasoning Result in ‘Right’ Results? At What Cost?” Peabody Journal of Education 79, no. 1 (2004): 7–35.

- Sunderman GL, Kim JS. The expansion of federal power and the politics of implementing the No Child Left Behind Act. Teachers College Record. 2007;109 (5) :1057-1085.

- Klein, A. (2020, November 29). ESEA's 50-year legacy a blend of idealism, policy tensions. Education Week. Retrieved July 2, 2022

- Bassok, D., Cellini, S. R., Hansen, M., Harris, D. N., Valant, J., & Wong, K. K. (2022, January 7). What education policy experts are watching for in 2022. Brookings. Retrieved July 2, 2022

- Datacenter.kidscount.org

- nces.ed.gov